Atticus Finch and the Discipline of Ethical Action

Few characters in American literature are as closely associated with moral courage as Atticus Finch.

Few characters in American literature are as closely associated with moral courage as Atticus Finch from Harper Lee’s 1960 novel, To Kill a Mockingbird. Yet what makes him a compelling study in praxis is not just that he stands up for what’s right, it’s how he does it: through deliberate reflection, ethical consistency, and a steady refusal to separate belief from behavior. He doesn’t just speak truth. He lives it, even when the consequences are personal and painful.

Practicing Phronesis in the Public Square

Aristotle’s concept of phronesis, or practical wisdom, is often contrasted with abstract knowledge. It is the kind of knowing that lives in action, especially in ambiguous or high-stakes situations. Atticus embodies this quality through his response to Tom Robinson’s case.

Tom, a Black man falsely accused of assaulting a white woman in a deeply segregated town, becomes the focus of the trial and the town’s ire. Atticus accepts the role of defense attorney knowing that he will be vilified for it. He tells Scout:

"Simply because we were licked a hundred years before we started is no reason for us not to try to win."

His belief in justice is not rooted in naivety. He understands the structural forces against him, yet proceeds with integrity. During his closing argument, he reminds the jury:

"But there is one way in this country in which all men are created equal — there is one human institution that makes a pauper the equal of a Rockefeller, the stupid man the equal of an Einstein... That institution, gentlemen, is a court."

He doesn’t take the case to win. He takes it because not doing so would fracture the integrity between what he teaches his children and how he lives. In a town full of people who say the right things but act otherwise, Atticus models praxis: ethical principles embodied in public action.

Reflection Before Action

Praxis is not impulsive. It is “thoughtful doing”. Atticus resists knee-jerk reactions, even under provocation. After the trial, Bob Ewell (humiliated by Atticus's quiet dismantling of his false testimony) spits in Atticus’s face on the street. Rather than retaliate, Atticus later quips:

"I wish Bob Ewell wouldn’t chew tobacco."

This isn't weakness. It’s deliberate self-restraint, anchored in his commitment to avoid escalating violence.

He also models reflection for his children. When Scout is confused as to why he’s defending Tom, Atticus tells her:

"If I didn’t, I couldn’t hold up my head in town, I couldn’t represent this county in the legislature, I couldn’t even tell you or Jem not to do something again."

This is not a lecture, but an invitation for Scout to understand that ethical action is more than a public show; it’s a continuous personal discipline.

The Praxis of Integrity

Atticus’s definition of courage frames much of the novel’s moral arc. He tells Jem, after Mrs. Dubose dies battling a morphine addiction:

"Courage is not a man with a gun in his hand. It's knowing you're licked before you begin but you begin anyway and you see it through no matter what."

This quote, while not about the trial, encapsulates his approach to the Robinson case. He defends Tom not for applause, but because doing anything less would violate the values he tries to instill in his children. His defense becomes a quiet, methodical form of protest against the inertia of cultural injustice.

After the verdict, the courtroom clears. As Atticus packs up his papers and walks out, the Black spectators in the balcony stand in silent respect. It is a haunting image of moral authority, even in defeat.

Cultivating Flourishing in Others

As a father and community member, Atticus aims not to impose values but to awaken them. He empowers Scout and Jem to think for themselves, guiding rather than dictating. He corrects them gently when they mimic the town’s racism or cruelty, asking questions instead of issuing ultimatums.

Miss Maudie, a neighbor and moral compass in her own right, observes:

"Atticus Finch is the same in his house as he is on the public streets."

This consistency is the heart of praxis. It allows his children, and others, to grow in an atmosphere where ethics are lived, not just spoken. He prepares them to confront the world’s cruelty with clarity and kindness.

An Enduring Example

In a world full of moral posturing and performative leadership, Atticus Finch endures as a figure of authentic praxis. He does not claim to be perfect. He does not dominate. He reflects, speaks carefully, and acts according to the ethical principles he holds most dear.

His legacy is not based on success in the courtroom, but on the way he shows up in every domain of his life: with integrity, restraint, and care. His story is a reminder that the strength of leadership lies not in authority or outcome, but in the consistent practice of what one believes, even when no one is watching.

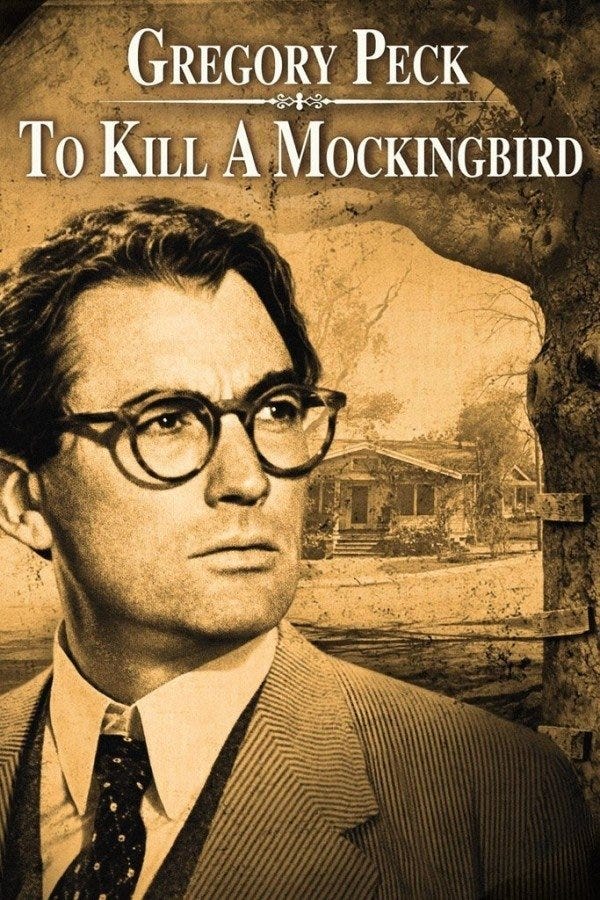

All film stills and promotional images from To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) are the property of Universal Pictures and are used here under the principles of fair use for the purposes of commentary, education, and critical analysis. No ownership is claimed by the author. If you are the rights holder and have concerns about the use of any specific image, please contact the author for prompt removal or adjustment.