Beyond Output

Why PDSA & Other Frameworks Fall Short Without Praxis

If you’ve worked in any sort of operational or corporate role, chances are high that you’ve come across the PDSA cycle—Plan, Do, Study, Act. It’s a mainstay in process improvement playbooks, tracing back to Deming and quality management. It’s tidy. It’s iterative. And it works, at least when the problem is optimization.

But lately, I’ve been thinking about what PDSA and other frameworks don’t ask. They don’t ask whether the thing we’re optimizing for is worth doing in the first place. They don’t ask what the process of achieving that goal turns us into. And they definitely don’t ask whether the goal, even when achieved, aligns with our values or larger purpose.

That’s where the distinction between poiesis and praxis becomes essential.

The Poiesis of PDSA

In Aristotelian philosophy, poiesis refers to productive action: work aimed at creating something external to the act itself. You write code to ship a product. You plan a marketing campaign to drive revenue. The value lies in the outcome, not in the doing.

PDSA fits this framework perfectly:

Plan: What do we want to achieve?

Do: Take action.

Study: Measure what worked.

Act: Adjust to do it better next time.

It is a cycle built to optimize performance toward a predefined output. Whether that output is a quarterly sales figure, a speed metric, or a cost-saving goal, the assumption is always the same: the goal is valid, the only challenge is execution.

This is not a criticism. In many domains, this mindset is essential. But when used as a total frame for leadership or organizational development, it starts to fail. Not because it is wrong, but because it is incomplete.

Enter Praxis

Praxis is action, too, but a very different kind. Aristotle used the term to describe ethical, intentional action whose value lies in the act itself. You act not to produce a thing, but to live out a belief. The goal of praxis is not an object, but a way of being in the world that aligns with values, character, and wisdom.

When leaders practice praxis, the question is not “Did we succeed?” but “Did we act with integrity? Did we embody what we stand for?”

PDSA looks at effectiveness. Praxis looks at alignment.

Praxis doesn’t reject learning loops, it thrives on them. But the cycle looks different:

Action: Take an intentional step based on values.

Reflection: Examine the results, and how the action aligns with your ethics.

Analysis: Consider alternatives, ethical trade-offs, and long-term implications.

Revision: Adjust not just the behavior, but sometimes the goal itself.

This is a deeper loop. It demands not just speed, but wisdom; what Aristotle called phronesis, or practical judgment developed through lived experience and reflection.

When Optimization Becomes a Liability

Let’s consider two versions of a company using an improvement cycle.

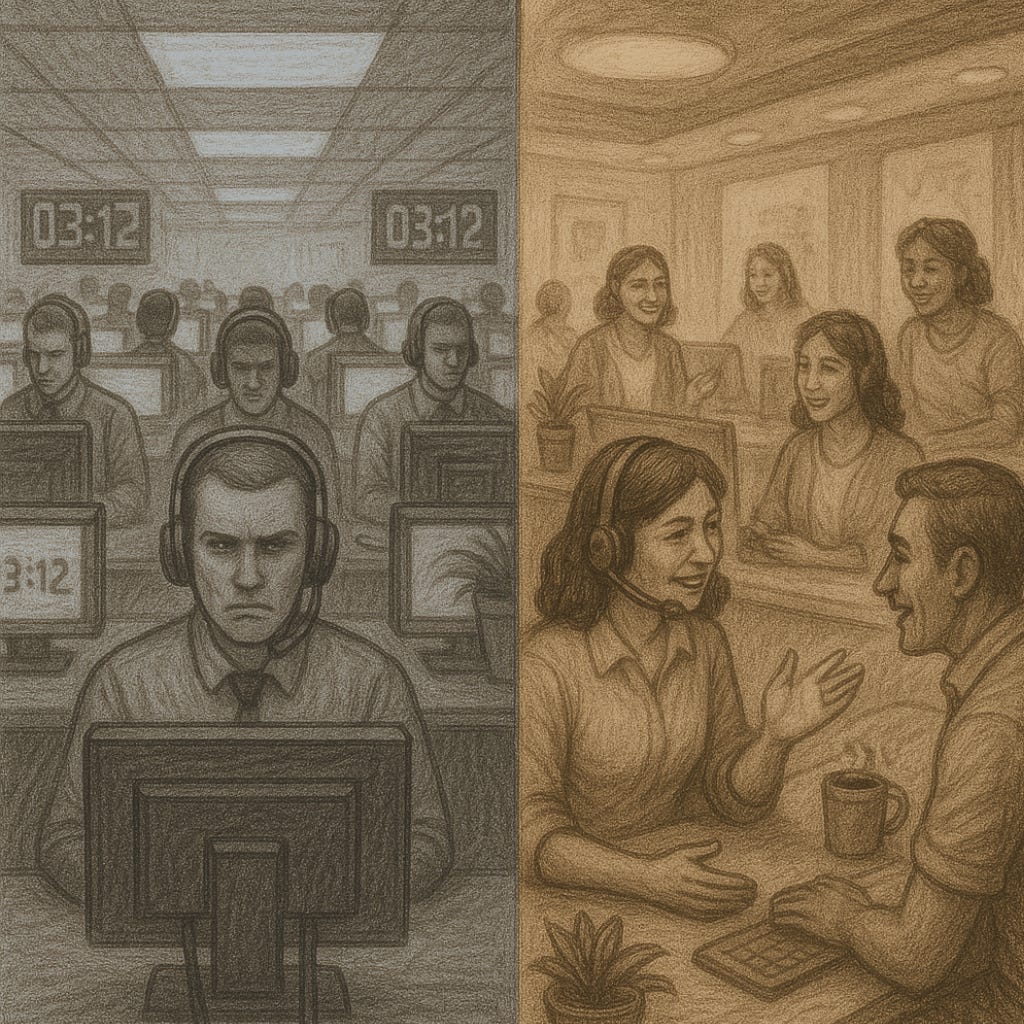

Version One (Poiesis-driven):

A customer support center uses PDSA to reduce average call time. They find a way to shave off 30 seconds per call by discouraging agents from making small talk or pausing for empathy. The metric improves. Leadership celebrates. Bonuses go out.

Version Two (Praxis-driven):

The same team reflects on the nature of customer support as part of the company’s stated mission to “empower people in moments of frustration.” In this frame, call time is only valuable if it coexists with empathy. They change the goal—not to minimize time, but to improve customer resolution satisfaction without harming emotional rapport. The optimization still happens—but in a new, ethically bounded direction.

In both cases, there is action and reflection. But only one asks if the goal should change. That’s the difference.

Finite and Infinite Games

James Carse’s concept of finite vs infinite games maps cleanly here (you may know Simon Sinek’s adaptation better). Poiesis is a finite game: you play to win, to hit a target, to be the best. The scoreboard is external and fixed.

Praxis is an infinite game. You play not to win, but to continue playing in ways that are meaningful, ethical, and aligned with your purpose. The scoreboard is internal. The “victory” is integrity.

If your company’s improvement cycles are driven by poiesis alone, you might get better and better at something that ultimately doesn’t matter, or worse, something that quietly erodes your values.

Reframing: Praxis-Informed PDSA

This doesn’t mean throwing PDSA out. It means upgrading it. Here’s how a praxis-oriented version might look:

Plan: Begin not with a goal, but with your values. What are we trying to become? What matters beyond efficiency?

Do: Take action consistent with both intention and ethical standards.

Study: Measure results, yes—but also look at the effects on people, culture, and trust.

Act: Adjust not just the method, but the meaning. Ask: Does this process still serve our purpose?

That’s how you blend process improvement with authentic leadership.

Why This Matters Now

As organizations lean harder into automation and AI — tools that accelerate poiesis — it becomes even more important to cultivate praxis. Machines are brilliant at optimizing for outcomes. They are terrible at judging what is worth doing in the first place.

Leadership, then, becomes not about doing things faster, but doing the right things: on purpose, in alignment, and with care.

Reflection is no longer optional. It is the defining differentiator in a world of increasingly commoditized action.

Add Praxis to Your Framework

PDSA, DMAIC, OODA loops, and Agile Retrospective Cycles are all powerful engines. But like all engines, they require a driver with a sense of direction. Praxis is that compass.

If your improvement loops leave you feeling efficient but hollow, you may not need better tools. You may need better questions.

And praxis begins with the most human question of all: What kind of person—or organization—are we becoming through our actions?

Thank you, @Glenn Stovall, for the great question that led to this post!