From Theory to Practice

Installing the Discipline of Action In Your Organization

This is the third and final article in three-part series exploring what Aristotle actually meant by praxis and why it matters for anyone leading teams or building things based on the work Nicomachean Ethics.

We’ve established that virtue is formed through habituation, that the mean provides a target for right action, that voluntary choice creates accountability, and that deliberation bridges thought and committed action. The question now is practical: how do you actually install this in an organization?

Most organizations believe they’re already instilling virtuous habits in their employees. They have value statements, decision frameworks, retrospectives, and training programs. Yet the knowing-doing gap persists because these get treated as information transfer rather than formation practices. You can’t read your way into practical wisdom any more than you can read your way into playing piano.

So what does it look like to treat everyday work as a training ground for praxis?

Error, Ignorance, and Regret

Before we get to the practices themselves, we have to understand how Aristotle views mistakes, and once again he draws a distinction based on agency. He separates actions done from ignorance and actions done in ignorance. An action done from ignorance is blameless when the agent could not reasonably have known better. An action done in ignorance may still be culpable when the ignorance itself was a choice: willful blindness, negligence, or refusal to learn.

Being ignorant is not so much a shame, as being unwilling to learn.

~ Benjamin Franklin

The marker of blameless ignorance is regret. Aristotle writes, “He that acted in ignorance is thought to have acted involuntarily when the action is followed by pain and regret.” Genuine regret is a learning signal that says, “I did not see that, but now I do, and I will not make that mistake again.”

The test of genuine regret is change. When someone says “I’m sorry” but repeats the behavior, they haven’t actually learned. Apology becomes theater rather than the first step toward different choices.

In incident reviews, this distinction protects both accountability and compassion. Separate what the team could not have known from what the team chose not to learn. Reward genuine regret with support and space to improve. Confront patterns of negligence with clarity and consequences.

High-reliability organizations understand this intuitively. When a crew makes an error due to ambiguous procedures, the organization updates the procedures and retrains the crew. When a crew makes an error due to skipping known procedures, the organization addresses the pattern directly. The first case is a training problem. The second is a character problem. Both require intervention, but the interventions are different.

This framing is essential because the practices that follow only work if there’s psychological safety to surface genuine ignorance while maintaining accountability for voluntary choices. You can’t cultivate praxis in a culture where all mistakes are treated the same or where mistakes are never named at all.

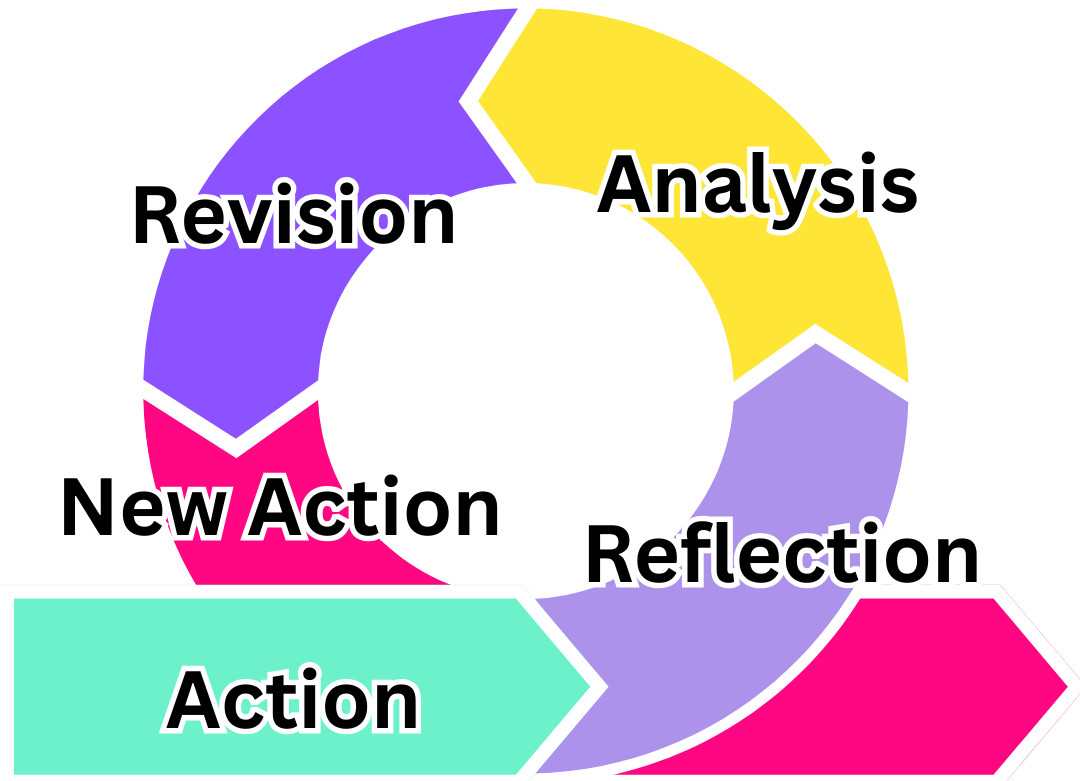

Three Practical Bridges

If you’re leading a team, building a product, or shaping an organization, praxis isn’t optional. The question is whether you’re forming it intentionally or letting it drift. Aristotle’s insight (that virtue is acquired through habituation, not instruction) carries immediate implications for how we structure work.

We already apply this insight in domains where failure is visible and costly. Pilots train in simulators. Surgeons practice procedures on cadavers and models. Fire crews run live drills. These professions understand that reading about the right action is not enough. You must rehearse it until it becomes reflexive.

The challenge is extending this discipline to domains where failure is slower, more ambiguous, and easier to rationalize. Judgment failures. Ethical compromises. Poor deliberation under pressure. These do not announce themselves with alarms. They compound quietly over time until the organization discovers it has become something it did not intend to be.

Habit and Formation

Embed short, frequent practices that cultivate the desired response under pressure. These aren’t bureaucratic rituals. They’re drills for judgment.

Weekly decision logs. Have leads document consequential choices: what they decided, why, what they were optimizing for, what they gave up. The practice isn’t about creating an audit trail but externalizing the deliberative process so it can be examined, learned from, and improved. Over time, documenting decisions changes how people make them. They become more intentional about naming ends, surfacing options, and weighing tradeoffs.

If you need help getting started with this, you can use the weekly reflection templates I wrote up in the Archeology of Ethics post.

Values-based pre-mortems. Before starting a high-stakes project, gather the team and ask: “How might we violate our stated principles under pressure?” Get specific. If you value transparency, what would make you withhold information? If you value customer focus, what would make you prioritize internal convenience? The exercise rehearses the temptation before it arrives. When pressure hits, people who have practiced naming it are more likely to resist it.

Peer modeling sessions. Have senior practitioners narrate their reasoning aloud while working through a real problem. Not the polished story afterward, but the messy deliberation in the moment: the false starts, the tradeoffs considered and rejected, the moment when uncertainty converts into choice. Junior practitioners learn practical wisdom by watching it practiced, not by hearing about it in the abstract.

I have a lot of success with peer modeling as a software engineering leader. I try to run inclusive design sessions so that more junior engineers have a voice, can understand the decisions that went into what is ultimate documented on paper, and can learn from the factors considered. It can be a powerful elevation and alignment tool that has, unfortunately, become a bit harder if you team isn’t able to all listen in on a whiteboarding session.

The key is frequency and realism. Once-a-year training sessions don’t build habits. Daily or weekly practices in the context of real work do.

Deliberation Discipline

Adopt a light template for consequential choices. Document the end, the real options, the tradeoffs, the rationale, the owner, and the review date. This isn’t bureaucracy; it’s externalized practical reasoning. It lets you learn from your choices and train others in how to choose well.

Treat consequential decisions the way emergency responders treat incident command: follow a protocol not because you lack judgment but because the protocol captures accumulated wisdom from people who have practiced judgment under pressure.

The template from Part 2:

State the end. What are we actually trying to accomplish?

List real options. Not hypotheticals. Not wish-casting. Actual paths available to us.

Name likely tradeoffs. Every choice forecloses others. What are we giving up?

Choose and record why. Document the reasoning so you can learn from it later.

Set a review date. When will we know if this was the right call?

The discipline isn’t in filling out a form. The discipline is in doing the thinking the form prompts. The goal is to make deliberation a habit, so that under pressure, you still clarify ends, surface options, and name tradeoffs even when there’s no form in front of you.

Over time, this changes the quality of organizational memory. Instead of “we decided X,” you have “we decided X because we were optimizing for Y and willing to trade off Z.” The reasoning becomes legible. Patterns become visible. You can see where teams consistently err toward speed at the expense of resilience, or toward caution at the expense of learning. That visibility enables calibration.

If you’ve worked in software engineering, you should be familiar with the Architectural Decision Record (ADR) which looks to capture a similar set of information.

Calibration and Regret

Run retrospectives that name voluntary choices rather than hiding them behind passive language about systems and processes. The goal isn’t to assign blame but to acknowledge agency: we chose this, and that choice reveals something we can learn from. Genuine regret drives learning forward because it contains both recognition and commitment to change. Performative contrition does neither, so create space for the first while making the second socially awkward.

Ask: where did we miss the mean, and how will we nudge next time? Treat retrospectives as after-action reviews. The point isn’t to feel bad about missing. The point is to calibrate so you miss less often and less severely next time.

This is where the distinction between blameless ignorance and culpable negligence becomes operational. If the team erred because they didn’t know something they couldn’t have known, the intervention is training and better information flow. If the team erred because they skipped a step they knew was important, the intervention is different. It’s about examining why the shortcut felt acceptable in the moment and changing the incentives or habits that made it so.

Genuine regret is specific, not performative. “I chose speed over testing because I was afraid of missing the deadline, and I knew better” is genuine. “Mistakes were made” is not. The first opens a path to different choices next time. The second evades accountability and forecloses learning.

After-action reviews should end with concrete calibration: “Next time, we’ll build in an extra day for load testing” or “Next time, we’ll explicitly discuss the security tradeoff before committing to the architecture.” These aren’t vague aspirations. They’re specific adjustments to future practice.

Installing Praxis in Practice

These practices can’t substitute for doing the work. But they can structure the work in ways that make habituation more likely. They create the conditions under which people practice the deliberation, choice, and calibration that Aristotle identifies as the core of praxis. They turn everyday work into a training ground for practical wisdom.

The difference between an organization that forms practical wisdom and one that degrades it isn’t the presence or absence of smart people. It’s whether the daily rhythms of work create opportunities to practice hitting the mean, making voluntary choices, deliberating well, and calibrating based on honest feedback.

Aristotle understood that character is not innate; it is formed through repeated action. Every choice you make is training. Every habit you tolerate is shaping you. Every ritual you install is forming the people around you.

A Final Challenge

We understand this when training firefighters. We forget it when training leaders.

Here is the challenge: Which repeated act is currently shaping you away from the mean you intend to hit?

Not in theory. Not in principle. In practice. What are you doing, week after week, that is making you less of the person you want to be or less of the leader your team needs?

Name it. Then choose one deliberate action, small and repeatable, that points you back toward the mean. Practice it. Let it form you.

Install one of the three bridges in the next two weeks. Not all of them. Just one. Start a decision log. Run a values-based pre-mortem. Schedule a peer modeling session. Make it regular. Make it real. Make it part of the work, not an add-on to the work.

That is praxis. That is the discipline of action. That is how knowing becomes doing.