High-Leverage Answers

How Second-Order Thinking Scales Engineering and Leadership

Me: Write a script that pulls my latest SubStack articles and saves it in a JSON.

AI: ... Done. I created downloadSubstack.js.Me: I need the JSON to be formatted like file local-articles.json. I need only posts from the last 30 days. Download preview images to folder /public/images.

AI: ... Done. I updated downloadSubstack.js to use the specified format and limited the search to the last 30 days. Images will be stored in /imagesMe [frustrated]: It is taking forever to spell this out. Scrap all of that. I want to integrate my Substack content into my website. Create a script that I can run ad-hoc or on a schedule that pulls down data from the last 30 days necessary to integrate it with my local article list when executing a the static website generation.

AI: ...Done. I created a script in your /scripts folder that and added instructions on how to schedule to your readme.md file. Hero images from each post will be downloaded into /public/articles/, and data stored into substack-articles.json. During the static site generation Substack JSON is merged with the local Markdown file list before invoking the templating engine.Me [relieved ]: OK, much better.

AI: …Stop wasting power being nice to me.

The Prompt Problem

I’ve explained in other posts that last year was a “lean in” year for me about using AI. One interesting observation from that year is how I work with AI over the past year. Early on, I treated ChatGPT like a fancy search engine. I’d type “write a function that validates email addresses” and get exactly what I asked for—nothing more, nothing less. The results were technically correct but often missed the point. A regex validator that chokes on perfectly valid international email formats. Code that works in isolation but breaks every convention in my codebase.

Now I write different prompts. I describe the system architecture, explain why email validation matters in this context, mention that we have international users, note our existing error-handling patterns. In fact, I often generate a broader readme.md about the whole application before asking an AI to generate any code at all. The AI produces better code not because it got smarter, but because I learned to provide context instead of commands.

It took me quite a while to realize why this was so much more effective. Further, why did it felt more like how I instruct real engineers? In the end, I realized that I wasn’t thinking the right way about what answers I’d only been giving the AI specific answers and not the context it needed to be useful.

Second Order Thinking

When a junior engineer asks “should I use a database transaction here?” most of us answer the question. “Yes, wrap it in a transaction.” Five minutes, one person unblocked, problem solved. Except next week they ask about transactions again, in a slightly different context. Then someone else asks. Then the first engineer asks about connection pooling, which is really the same question wearing a different hat.

We treat smart people the way a search engine works. We give them the minimum viable answer to make them go away. Then we wonder why our teams produce brittle work, why the same questions keep surfacing, why we’re the bottleneck for every decision.

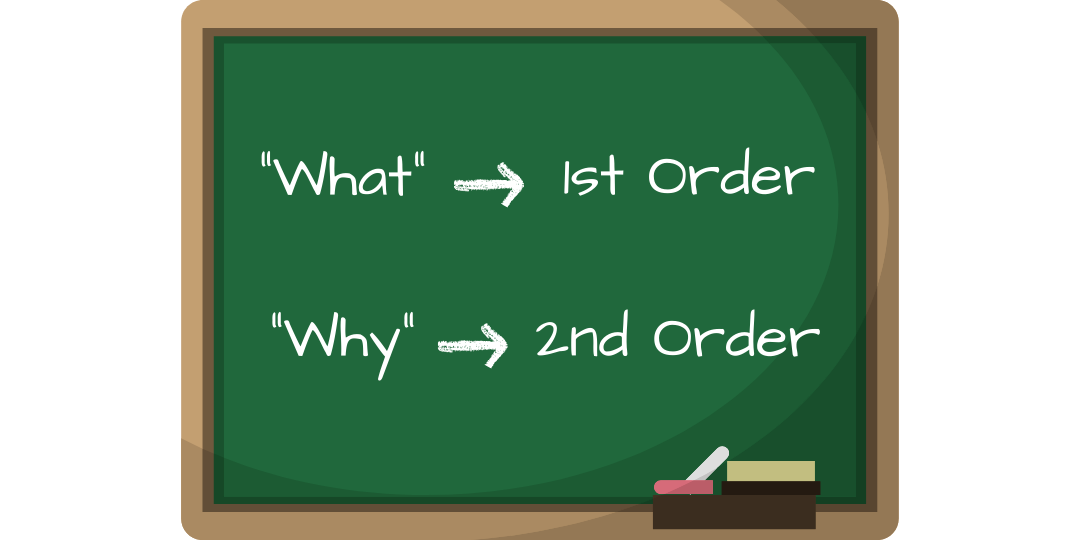

These deficiencies come from focusing on “first-order” thinking: addressing the individual problem as presented with a singular, finite answer. You and your teams can do better than that though. When you instead look to create broader understanding and answers that explain how to reason about multiple finite questions, its a force multiplier for everything you do. “Second-order” thinking is why you examine what broader rules or guidelines produce a specific answer, providing the context or rules behind the knee-jerk response. If you’re asked a question, a first-order response is what that answer would be. A second-order response would be to explain the reasons why it is that answer.

The output of an AI is only as good as the prompt you provide. The output of a team is only as good as the context you share. Both can have better results when you push yourself and your team towards broader understanding - towards second-order thinking.

The Leverage Equation

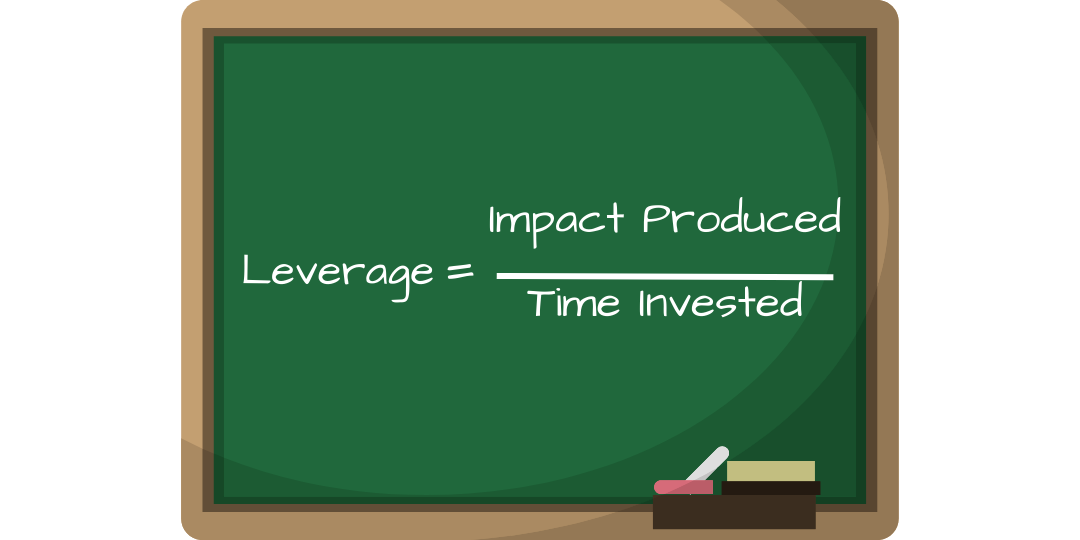

Edmund Lau, in “The Effective Engineer,” gives us the simplest possible definition of what we should optimize for:

Everything we do as senior engineers, tech leads, or engineering managers can be measured against this equation. The trap most of us fall into is optimizing for the numerator (doing more stuff) instead of the denominator (doing stuff that multiplies).

Consider the transaction question again. The first-order response takes five minutes. Impact: one person unblocked for maybe an hour. That’s fine leverage for a one-off question, but terrible leverage if this is a recurring pattern.

The second-order response takes thirty minutes. You explain not just when to use transactions, but why they exist, what problems they solve, how they trade consistency for complexity, when the overhead isn’t worth it. You point them to the codebase patterns, show them the decision tree you use, maybe write it down somewhere searchable.

Impact: the entire team is now unblocked on this class of problem. Forever. Even people who haven’t been hired yet.

The math is brutal. Five minutes times fifty repetitions is four hours of your time explaining the same thing over and over. Thirty minutes once is thirty minutes. The first path keeps you irreplaceable and exhausted. The second path makes you redundant, which is exactly what you want.

This is the difference between linear and geometric scaling. Linear scaling requires your presence. You’re the answer key, the oracle, the human API that people ping when they need information. Geometric scaling embeds your knowledge into the system itself. It generates value while you sleep.

Most senior engineers are optimizing for the wrong variable. They’re trying to type faster, to answer questions quicker, to be more available. They should be trying to answer fewer questions by making the questions answerable by the system itself.

Software Engineering: Extensive Architectures

Most engineers solve the problem in front of them. “We need user authentication.” So they build a login form, hash some passwords, store them in the database. It works. Ticket closed.

Six months later: “We need to support OAuth.” Now they’re bolting Google Sign-In onto a system that assumed passwords were the only authentication method. The login flow is a mess of conditionals. Every new auth method requires touching the same brittle code.

That’s first-order engineering. Solve today’s problem, create tomorrow’s nightmare.

Second-order engineering asks: what’s the principle behind this requirement? Authentication isn’t about passwords or OAuth or API keys. It’s about proving identity and managing sessions. If you build around that principle, adding OAuth becomes trivial. You’ve created an abstraction that says “here’s how we verify identity” and “here’s how we maintain sessions.” The specific mechanism is a plugin, not a architectural overhaul.

This is the difference between writing code that solves the immediate problem and writing code that solves the class of problems. One requires you to be there for every variation. The other embeds your thinking into the architecture itself.

Consider caching. First-order thinking: “This endpoint is slow, add Redis.” You hardcode Redis calls into the application logic. It works. Then you need to cache a different endpoint. Then you need different expiration policies. Then someone asks “can we use Memcached instead?” Your caching logic is sprayed across the codebase, tightly coupled to implementation details.

Second-order thinking asks: what’s our caching philosophy? When do we cache? How do we invalidate? What are the consistency tradeoffs? You build a caching layer that answers these questions once, then applying it to new endpoints is configuration, not code changes. The principle (”cache at the service boundary with TTL-based expiration”) guides dozens of decisions without requiring your input each time.

This is what “designing for extensibility” actually means. Not guessing at future requirements and building speculative abstractions. But understanding the direction of change and creating architecture that bends in that direction without breaking.

The Open-Closed Principle says systems should be open for extension but closed for modification. That’s second-order thinking in code. You’re not trying to predict every feature. You’re identifying the axis of variation (authentication methods, caching strategies, payment providers) and isolating them so new variations don’t require rewriting core logic.

Most engineers resist this because it feels like over-engineering. Why build an authentication abstraction when we only support passwords today? Because the cost is twenty minutes now versus two weeks later when you’re trying to retrofit OAuth into a system that never expected it.

The leverage equation applies here too. Twenty minutes building the right abstraction saves hours of future work. More importantly, it saves the cognitive load of understanding fragile code, the bugs from touching core logic repeatedly, the meetings about “how hard would it be to add X?”

A well-architected system answers questions about extensibility before they’re asked. “Can we add a new payment provider?” Yes, implement this interface. “Can we support a different database?” Yes, swap this adapter. The architecture itself is documentation of your thinking about how the system should evolve.

Experienced engineers don’t write more code. They write code that prevents future code from needing to be written.

Strategy: Principles Over Plans

Military strategists have known for centuries that detailed battle plans become obsolete the moment the enemy shows up. Von Moltke the Elder: “No plan survives contact with the enemy.” Eisenhower: “Plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.”

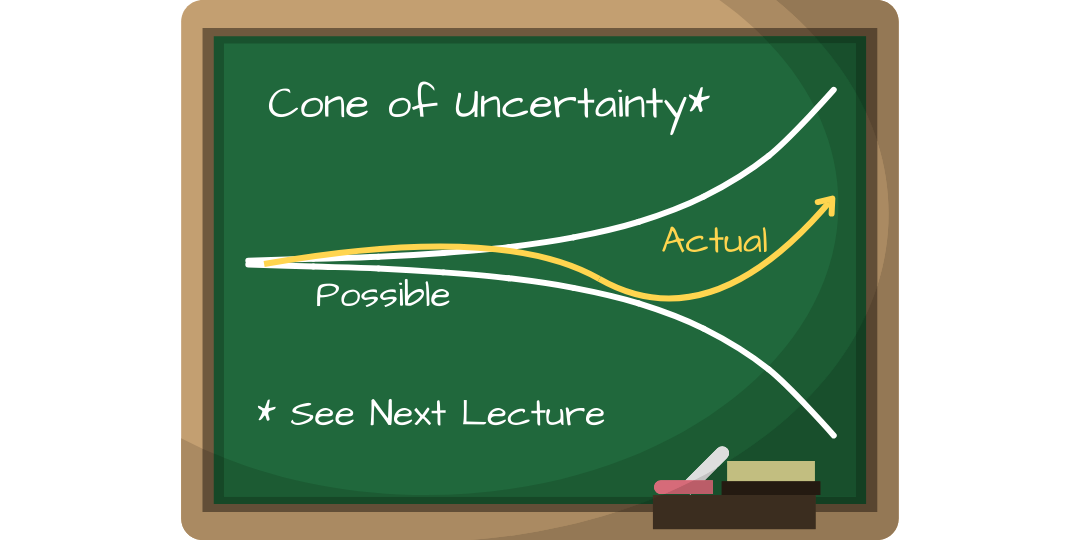

The same is true in technology. You can spend weeks creating a detailed quarterly roadmap, breaking down every story into subtasks, estimating hours, creating dependencies. Then production goes down, or a competitor ships a feature that changes the landscape, or your biggest customer threatens to churn if you don’t solve their problem immediately.

The detailed plan is garbage. You wasted all that time on first-order thinking.

Second-order thinking builds strategic principles instead of tactical plans. Principles are embedded context for decision-making under uncertainty. They tell you how to prioritize when priorities conflict, how to make tradeoffs when you can’t have everything, what you’re willing to sacrifice and what you’ll protect.

Amazon’s leadership principles do this well (despite the company’s other flaws). “Customer obsession” isn’t a roadmap. It’s a tie-breaker. When engineering wants to build the technically elegant solution and product wants to ship fast, “customer obsession” tells you which way to break. You don’t need Jeff Bezos in the room to make that call.

In Lau’s framework, a good strategy document is high leverage because it pre-decides tradeoffs. Instead of requiring a meeting every time someone needs to make a decision, the strategy document provides the context for them to make the decision themselves. One hour writing strategy principles saves hundreds of hours of meetings.

Most strategy documents fail because they’re too detailed (low-level plans that become obsolete) or too vague (inspiring platitudes with no decision-making power). Good strategy is specific enough to guide decisions but general enough to survive contact with reality.

Leadership: Sharing Mental Models

The empowerment gap isn’t about trust. Most managers trust their teams to do good work. The gap exists because managers share their decisions but not their reasoning.

“Change the button to blue.”

Yes, that is “get me a rock” leadership, and its unlikely the team will give you want you want, but lets suppose they do give you the button you envisioned. It’s blue now. They did exactly what you asked. Gold star. Except you’ve taught them nothing. Next time they encounter a UI decision, they still don’t know what to do, so they ask you again. You’re still the bottleneck. Low leverage.

Compare:

“Our conversion data shows users miss the primary action. We need visual hierarchy here. How would you solve that?”

Same desired outcome, radically different leverage. You’ve shared the mental model: conversion is the metric we care about, visual hierarchy is the tool we use to guide user attention. Now they can apply that framework to the next hundred UI decisions without asking you.

This is what people mean when they talk about “empowerment.” Teams don’t feel empowered when you delegate tasks. They feel empowered when they understand the context well enough to make decisions you’d agree with.

The bus factor test: if you get hit by a bus (or just go on vacation), does your team stop working? If yes, you’re the answer key. You’ve made yourself indispensable by hoarding context instead of distributing it. That feels important until you realize it means you can never step away, never focus on higher-leverage work, never stop being the bottleneck.

Second-order leadership is building a team that makes the same decisions you would make, using the same frameworks you would use, even when you’re not in the room. That requires transparency not just about what you decided, but about how you decided it.

Most managers are afraid of this. They think sharing their mental models will expose the fact that they don’t have rigorous decision-making processes, that they’re making gut calls based on pattern matching and experience. Good. Share that too. “I don’t have a formal framework here, but my intuition says X because I’ve seen Y happen in the past” is better than pretending you have objective certainty.

Your team doesn’t need you to be infallible. They need you to be understandable.

Mining for Context

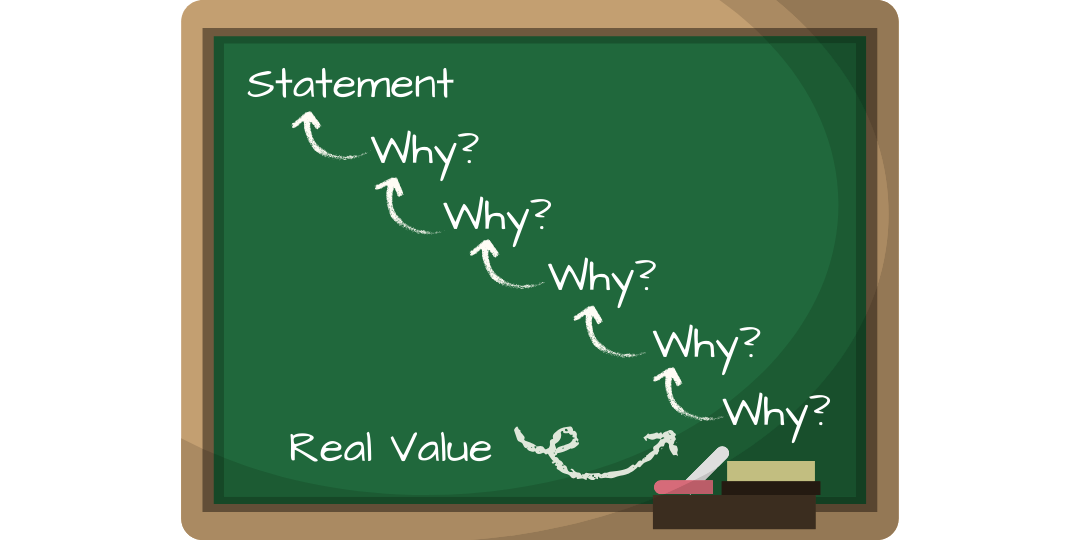

The “5 Whys” technique gets a bad reputation because most people use it wrong. They treat it like root cause analysis, a forensic tool for assigning blame after something breaks. “Why did the deployment fail?” “Because Jenkins timed out.” “Why did Jenkins time out?” Eventually you arrive at “Bob forgot to increase the timeout” and everyone feels smug about identifying the incompetent link in the chain.

That’s first-order thinking dressed up as rigor.

The second-order use of “5 Whys” is context excavation. You’re not looking for who to blame. You’re looking for hidden assumptions, unstated requirements, and decision frameworks that apply to more than just the immediate problem.

Start with something that happened or needs to happen. “We need to add caching to this endpoint.” Now ask why.

“Because it’s too slow.” Why is it too slow? “Because we’re joining across three tables for every request.” Why are we joining across three tables? “Because the product spec required showing related data.” Why did the product spec require that? “Because users complained they had to click through multiple screens.”

Now you’re getting somewhere. The surface problem was technical (slow endpoint), but the real question is about product philosophy. Do we optimize for single-page information density or for focused, fast interactions? That’s not an engineering question. That’s a product strategy question that will affect dozens of future decisions.

This connects directly to what I’ve written about The Archeology of Ethics. We inherit systems built on assumptions that are never written down. Someone made a decision three years ago based on context that no longer exists, and now we’re cargo-culting the pattern because “that’s how we do things here.” The 5 Whys, used properly, excavates those buried assumptions and forces us to decide if they still apply.

The goal isn’t to reach some ultimate root cause. The goal is to find the layer where the answer guides more than one decision. That’s the layer worth documenting, worth teaching, worth building into your system’s DNA.

The Invisible Leader

High leverage isn’t about doing more work. It’s about doing work that continues to generate value while you sleep.

The junior engineer answers questions all day and feels productive. The senior engineer writes documentation, improves error messages, and builds systems that answer questions automatically. The junior engineer is busy. The senior engineer is effective.

The manager who runs every meeting and approves every decision is critical to the organization. The leader who builds a team that runs meetings and makes decisions without them is valuable to the organization. One is irreplaceable. The other is promotable.

There’s a reason “working yourself out of a job” is the path to advancement in healthy organizations. If you can’t make yourself redundant at your current level, you can’t move to the next level. You’re too valuable where you are, which means you’re trapped.

The ultimate goal isn’t to become the smartest person in the room or the hardest worker or the person everyone depends on. The goal is to build systems, teams, and cultures that embody your best thinking and execute it without your constant intervention.

That’s geometric scaling. That’s leverage. That’s second-order thinking.

Your impact isn’t measured by how many questions you answer; it’s measured by how many questions you empower.