Put the Right Thing First

Your documentation might be 100% accurate and still completely fail your readers. The problem isn't what you're saying, it's how you're saying it.

My friend Leslie Neal and I were chatting recently about the role of storytelling and narrative control when designing presentations, and how the type of presentation and your goals for it should shape the narrative. I’ll leave Leslie to be the expert in doing that for presentations, but it did make me start thinking about how many technical documents I’ve read that could use the same perspective.

The distance between a technical document and a presentation isn’t vary far in some cases, and even when it is, thinking about the reader and the narrative you want to create for them is always the right decision.

When Good Docs Go Bad

Your documentation might be 100% accurate and still completely fail your readers. The problem isn't what you're saying, it's the way you’re communicating with the reader. A document that starts with a wall of configuration steps, buries the main payoff, or leads with exotic edge cases leaves readers adrift. You’re document might have all the information right there but no one ever seems to see it because you didn’t provide a logical flow they can follow.

If you feel that you already have explained it all, chances are that your document isn’t missing information, its missing story telling, and in documentation, storytelling means sequencing information.

Sequencing is a deliberate decision based on the reader's needs. We don’t write technical docs to entertain, but we still need to guide. Readers need orientation before detail, context before commands, and resolution before they can move on. The best documentation feels like being led down a well-marked path: every turn arrives just as the reader expects it, no sooner and no later. That flow is the story. Sure a user might want to skip some parts, but that is what indexes and tables of contents are for - your job is to guide someone from start to finish.

Different Paths for Different Goals

Not every reader wants the same path. Sometimes the right move is to start with why (a clear purpose) before introducing the components and steps. Other times, especially in tutorials, the most respectful thing you can do is give them a quick win first, then build the concepts behind it. Troubleshooting guides demand a different rhythm altogether: you start with the symptom, explain the cause, then show the fix.

Architectural documents benefit from beginning with principles and constraints, then laying out the pieces, and only then diving into mechanics. Guides that help readers make choices work best when they start with the outcome, show the available paths, and highlight a recommended default.

The sequence isn’t arbitrary. It’s a deliberate decision based on what the reader needs most in that moment. That might even mean that you need more than one version of a document that covers the same information; your leadership is not going to need the same detail as your engineers.

Keeping Readers on Track

Good flow doesn’t happen by accident. It takes craft. Once you've chosen the right sequence for your readers' goals, specific techniques keep them moving smoothly through your content. Signposting (telling readers where they are and where they’re headed) reduces friction. Progressive disclosure (saving edge cases and advanced flags for later) keeps the happy path clear. Framing sections as answers to natural questions makes the logic visible: Why should I care? What is this thing? How do I use it? Who needs to act? When does it matter?

Although you have to approach each audience and situation individually, it can be important to establish consistency. When documents in a library follow similar rhythms, readers build confidence and move more quickly. That is why even though the information must be tailored to your audience, the sequencing may be the same for similar documentation for different groups.

Patterns That Shape Understanding

Different documents demand different rhythms. There is no single sequence that works in every case, but a handful of patterns recur because they align with how people actually learn.

Why → What → How

This is the classic explanatory arc. Begin with purpose so the reader understands the stakes; why this system, approach, or tool exists. Then move to the model: what the components are and how they relate. Only after that do you show the steps. For instance, an architecture overview might first explain why event-driven design supports elasticity, then define topics, subscriptions, and publishers, and finally demonstrate how to configure Pub/Sub in practice.

Examples → What → How → Why

Tutorials often succeed when they deliver a small win early. Readers copy, paste, and run something that works before they understand it. That quick success builds confidence. The writer then circles back to explain what happened, how to extend it, and why the approach matters. A “Hello World” query in BigQuery that immediately returns results is more engaging than three pages of schema theory.

Problem → Why → Fix

Troubleshooting guides follow a different rhythm because the reader arrives with pain. The first step is to name the symptom clearly so they recognize it. The next step is to explain why it happens, which builds confidence that the diagnosis is correct. Finally, the document provides the fix. For example: “Error 429 indicates too many requests. This occurs because the service enforces a rate limit. To resolve it, adjust the retry budget and verify backoff.”

Principles → What → How

Architecture and policy documents often lead best with principles. By stating the design tenets or constraints up front (durability, latency, cost targets, etc), the reader understands why later choices were made. From there, the document outlines the pieces of the system and, last of all, describes how to implement them. This prevents debates that miss the context of the underlying goals.

Outcome → Paths → Recommended Default

Decision-focused documents benefit from naming the goal first, then exploring the available paths, and finally marking a preferred route. Readers know immediately what they are aiming at, what their options are, and which one the author considers safest. For example: “Our objective is to reduce p95 latency by 30 percent. You could achieve this with caching, query rewriting, or parallelization. We recommend starting with caching for product detail pages, with a default TTL of 10 minutes.”

One of My Defaults

Because consistency is key, I often follow a similar template when writing documents, paying attention to address the intended audience within that framework. On example of that is what I have come to call a “Solution Proposal,” which is in some ways similar to a Amazon’s “6-Pager” format. I use it whenever I need to frame up a decision about how to solve a problem.

Solution Proposal Template

# Problem Title - “Content Management Server Performance Improvements”

Make sure you title this with a descriptive name that partners and stakeholders will understand so that they can refer to this document by name and easily find it within whatever document repositories you use.

## Business Problem

Describe the business problem in detail, covering the current issue and expected outcomes at a high level. I specifically make sure to pose this as a “business” problem because it forces me to think about the value to the business. It is easy to think that server performance issues aren’t a business problem, but because the work it takes to resolve the problem has to be evaluated against other business priorities such as new features, its best to frame things from that perspective right off the bat.

### Considerations

A bulleted list of information that the reader needs to establish context, such as existing systems, contact details, and other nonfunctional requirements. This can be broken up into subsections based on the complexity of the context.

### Goal(s)

Clearly list the acceptance criteria that must be met for this solution to be considered complete. This can be KPIs or outer business metrics or reiteration of constraints created by the listed Considerations.

## Current State

Here I spend time to explain how related roles, processes, and systems work today, including diagrams and other supporting information. This serves as a grounding for understanding later options. Often, this section includes subsections specifically relevant to that document, such as information on system performance, costs, or scalability.

## Proposed Solution

Next, I discuss what I propose should be done to address the Business Problem, including enough information for the reader to understand the proposal. Its OK if you leave some details out though; you’ll have a chance in the Options Considered section to make sure all of the details are fully spelled out. You’ll usually want to address the same considerations you created sections for in the Current State section here though.

It might surprise you that I would jump to this now, when I put the information on how I selected this option after the recommendation, but this is because most people reading a document want to know what what you are advising them to do, and they wont want to be confused by having tons of options presented to them if those options have already been eliminated.

If you’re still working on what that proposed solution actually is, then you can just put a [TBD] here and move on. If you do have a proposal and are confident in its strength, include a link to skip down to the Implementation Plan so readers who are already bought in at this point can skip to how to help.

### Reasoning

In this subsection I make sure to address all of the ways that this solution addresses (or does not) everything listed in the Business Problem, including the Considerations and Goals. This will naturally lead into questions about other options considered and trade offs.

## Options Considered

### Option Name - “Increase Server Resources”

Now I get into listing each option I considered, making sure to include the necessary diagrams, contract samples, and other artifacts to help the reader understand how this solution would function. This should include the one you have given as your Proposed Solution.

#### Pros/Cons

For each Option Considered, you should create a Pro/Con list that addresses all of your considerations and also addresses operational concerns such as costs, support, delivery time, team dependencies, etc. This is your chance to really hype or bash each option.

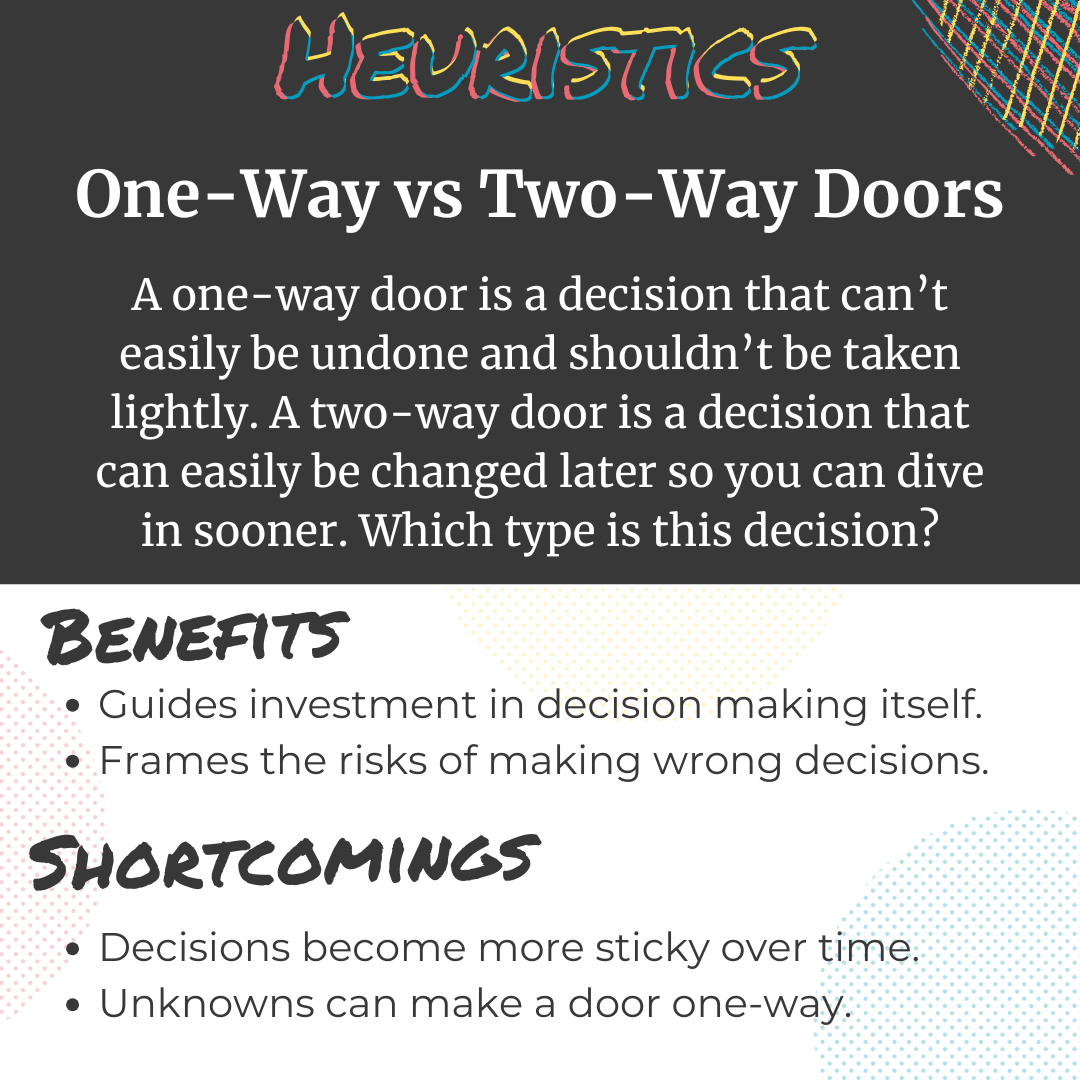

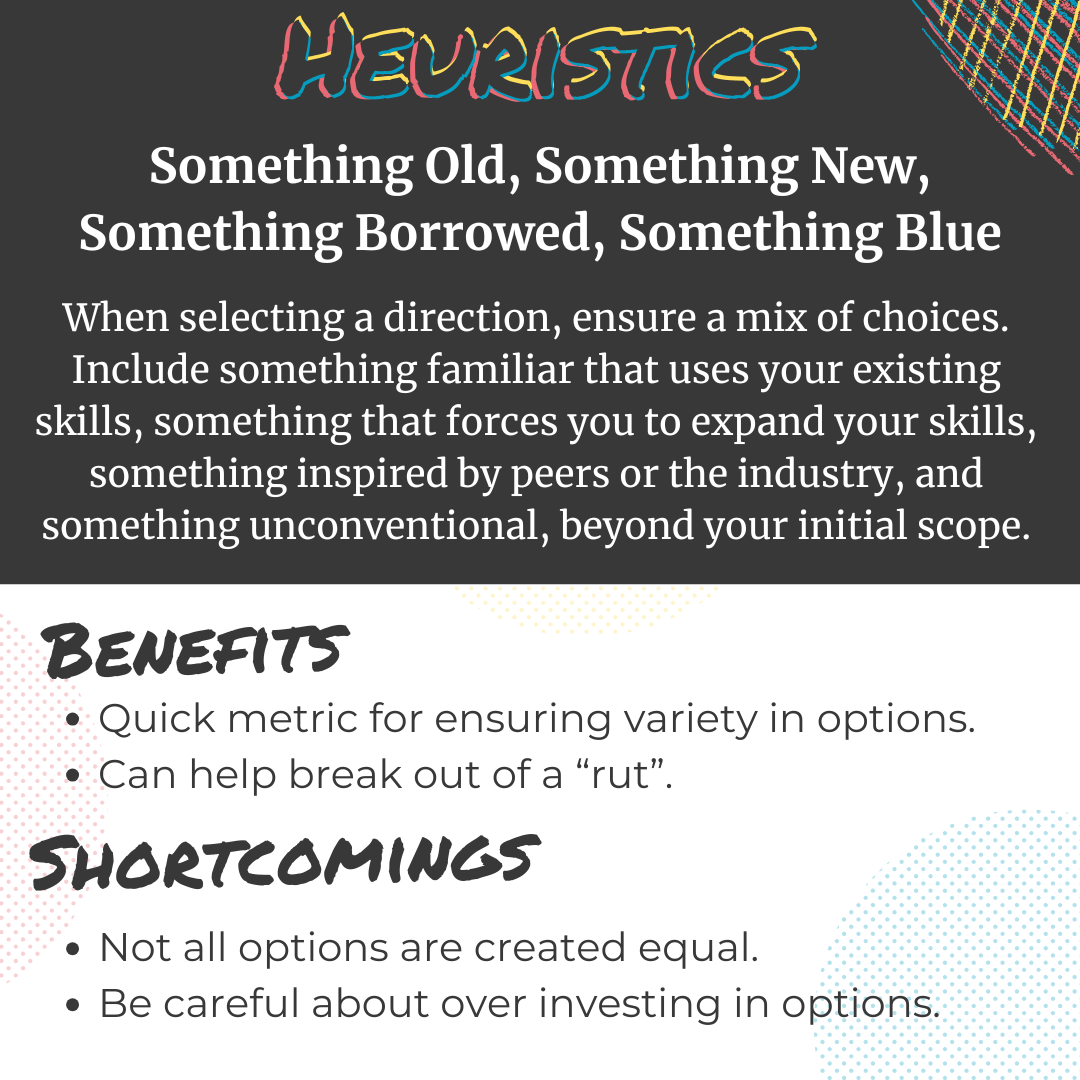

Ideally, you should have at least three options in every situation, but I often like to have more. There is a limit to what people will understand though, so if you find yourself juggling dozens of options, you’ve probably got to get a better understanding of your Considerations and then do some quick work to winnow out which ones are really just not work treating as legitimate options. If necessary, push them to a supplemental document so everyone knows you didn’t just ignore that idea though.

## Implementation Plan (optional)

At this point, if you have a solid proposal you should be working to create a call to action for your readers by laying out a path to implementing your proposal. This should include impacts or ask for specific teams, a description of the sequence required to implement the plan, and a clear reiteration of any blockers that require resolution to move forward. Don’t forget diagrams here too - they can be a useful tool in establishing the relationships between teams or blockers or providing a Gantt timeline for implementation.

The Payoff of Sequenced Writing

When documentation respects order, comprehension accelerates. Readers hit useful milestones earlier. They adopt more quickly and ask fewer repeated questions. Most importantly, they trust the material. They feel that it was written for them, not for the author’s convenience.

That is the power of storytelling in technical writing.

Solid advice, love the different templates and approaches. It's like they used to say in the news paper: BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front)