The Hollow Performance of Dyspraxis

How organizations mistake ritual for progress and theater for substance.

The conference room hums with the familiar energy of strategic planning. Charts fill the whiteboard, laptops glow with spreadsheet tabs, and the leadership team leans over perfectly formatted OKRs. Each objective is specific, measurable, aligned with corporate strategy. The presentation slides are polished, the language crisp, the metrics clear.

But something is fundamentally wrong. They’re not setting goals—they’re retrofitting them. Every objective has been carefully crafted to justify work they committed to shipping six months ago. The quarterly review will celebrate “achieving” targets that were never really at risk.

This scene plays out in conference rooms everywhere, a ritual of strategic planning that produces all the right artifacts while draining strategy of its substance. Organizations adopt the form of best practices while discarding the thought that made them valuable. This empty mimicry creates what I call dyspraxis: a ritual of progress that delivers none of its substance.

The Substance Behind Best Practices

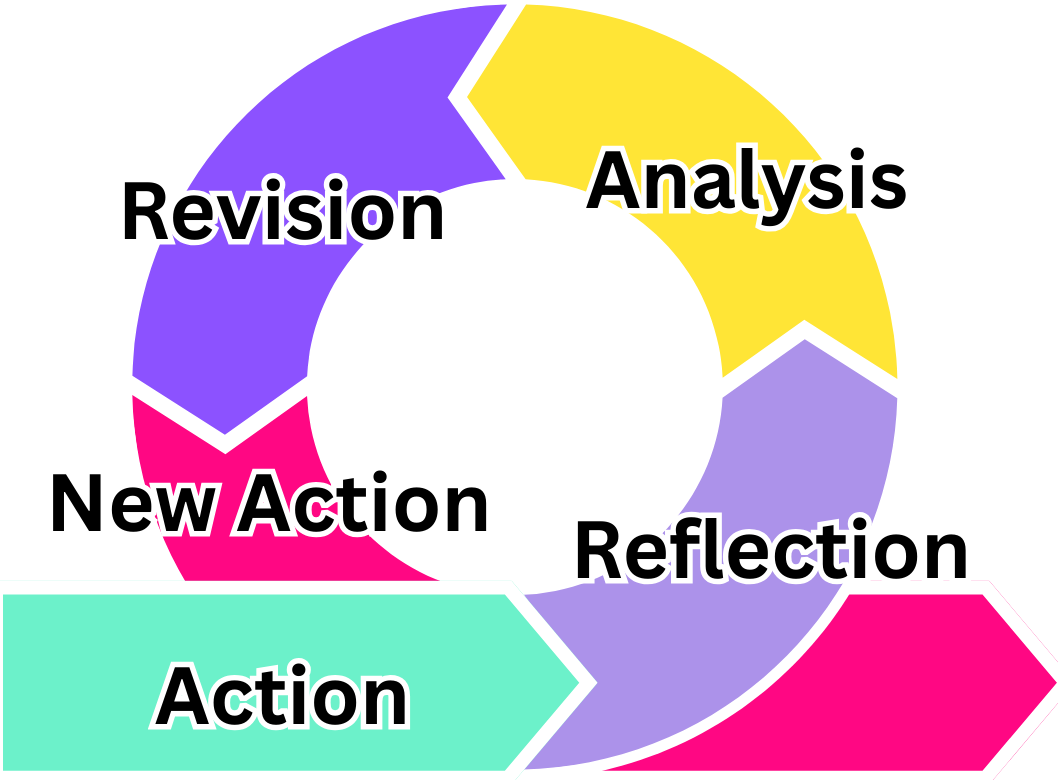

Best practices are not sacred templates. They emerge from hard-won lessons, cycles of reflection, and careful adaptation to specific contexts. Their true value lies in the reasoning that created them and the feedback loops that sustain them. Reflection leading to informed action. When copied as static checklists or rigid artifacts, best practices lose their force. They become theater, convincing from the outside but hollow within.

The danger is that this theater can be remarkably convincing. A backfilled OKR document looks identical to one born from genuine strategic thinking. The difference lies not in the format but in the process that created it and the learning it enables.

Aristotle and the Spectrum of Praxis

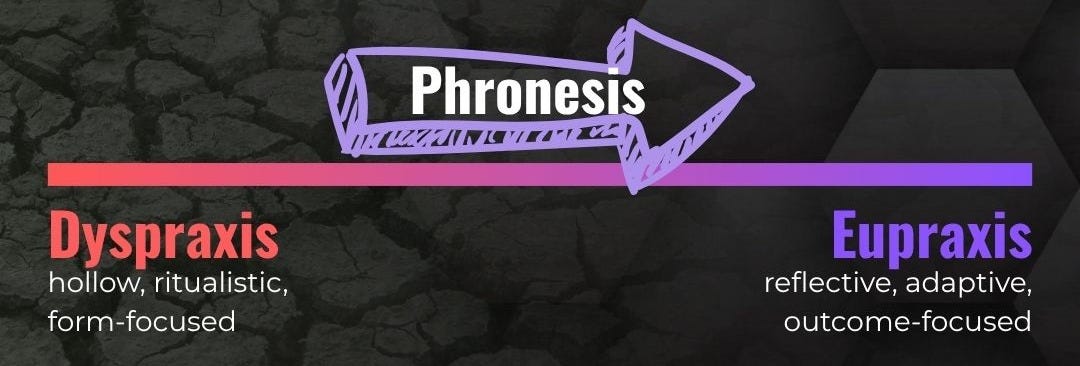

Aristotle gave us a useful vocabulary for thinking about action that applies remarkably well to modern organizations. Praxis was never just doing for the sake of doing. It was action guided by reflection, grounded in what he called phronesis (practical wisdom). A good leader was not the one who checks the most best-practice boxes, but the one who acted with intention, measuring outcomes against purpose; someone who follows form over function is not demonstrating phronesis.

In organizational terms, phronesis is the wisdom that asks not just “How do we implement this practice?” but “Why does this practice exist, and how will we know if it’s working?” It’s the difference between following a playbook and understanding the game.

From this foundation, we can think about two divergent paths:

Dyspraxis praxis. In Greek, the prefix dys- (δυσ-) means hard, ill, badly, or with difficulty. It connotes dysfunction, disorder, or being “out of joint.” It isn’t always morally bad — sometimes it means unfortunate, unlucky, or done poorly. Dyspraxis is the hollow performance of action, where the visible artifacts remain but the reflective wisdom has been discarded. A leadership team that backfills OKRs to justify already-determined deliverables is engaging in dyspraxis; it isn’t malevolent, but misaligned and unlikely to create benefits.

Eupraxis praxis. eu- (εὖ) means well, properly, in the right way. It carries a sense of flourishing, success, or harmony. It’s not just “good” in the moral sense, but more like “done fittingly” or “in accordance with its nature.” Eupraxis is action aligned with reason, ethics, and intention. A team that reflects on the meaning of their OKRs, adjusts them in light of changing context, and uses them to guide authentic decision-making is practicing eupraxis. The form and the spirit are intact.

What Aristotle reminds us is that the form is not enough. A ritual without reflection is not praxis but pretense. In organizations, dyspraxis breeds delusion because it looks like progress but hides the absence of growth. Eupraxis, on the other hand, is where best practices actually earn the name.

Dyspraxis At Work

These hollow performances take predictable forms across organizations. Teams craft OKRs that retrofit objectives to predetermined work, then celebrate achieving goals that were never genuinely at risk. Agile ceremonies become empty rituals where standups turn into status reports and retrospectives cycle through the same observations without ever changing behavior. Organizations implement measurement frameworks that track activity rather than impact, optimizing for metrics that bear little relationship to the problems they’re meant to solve.

In each case, the visible artifacts of good practice remain intact. The templates are complete, the meetings happen on schedule, the dashboards show green. But the substance has been drained away, leaving only the performance of progress.

The Cost of Dyspraxis

Dyspraxis creates the dangerous illusion of progress while real problems go unaddressed. Teams feel productive completing templates and attending ceremonies, but nothing actually improves. Resources get poured into optimizing processes that don’t matter while genuine issues remain invisible.

The human cost runs deeper. When teams see leadership more invested in the performance of practices than their substance, trust erodes and cynicism grows. People begin to view all organizational initiatives as theater, making future change efforts exponentially harder. The very practices meant to align and energize teams become sources of frustration and disengagement.

The Benefits of Eupraxis

Consider how a product team might practice eupraxia with retrospectives. Rather than following a rigid “what went well, what went poorly, what should we do differently” format, they adapt their reflection to what they’re actually trying to learn. After a particularly challenging sprint, they might focus entirely on understanding why their estimates were so far off. After a successful launch, they might examine what collaboration patterns worked well and how to replicate them.

The format serves the purpose, not the reverse. They track which action items from past retrospectives actually changed behavior and which were forgotten, using that meta-data to improve their reflection process itself. The retrospective becomes a living practice that evolves with the team’s needs rather than a ceremony performed for its own sake.

“Management is doing things right; leadership is doing the right things.”

~ Peter Drucker

How Organizations Become Dyspraxic

Most organizations don’t choose dyspraxis deliberately. They slide into it when external pressure to signal sophistication meets internal pressure for visible progress. Teams copy successful peers without understanding context or attempt to fit the “right” way to do something on top of a broken system. The connection between practice and purpose is broken.

“We’ll Do It Next Time”

The most common trigger I’ve encountered? “We don’t have time for that right now.” The organization feels pressure to deliver and decides that just this one time they can skip some steps. Everyone knows they aren’t supposed to, but it’s just this one time and they promise they will do it all the right way next time.

Except next time never comes. The shortcuts become the standard. The abbreviated process gets referenced as “what worked last time.” Soon, what started as an emergency exception becomes permanent practice, stripped of the reflection and feedback loops that made the original valuable.

“Fake It Until You Make It”

Some organizations adopt the visible forms of best practices believing this will naturally evolve into genuine implementation. The thinking goes: start with the templates, hold the meetings, create the dashboards, and eventually the substance will follow.

This approach fundamentally misses the point. The hard work isn’t in completing the artifacts—it’s in the reflection, adaptation, and honest feedback that gives practices their power. Skipping straight to the performance tricks teams into thinking they’re making progress while avoiding the very work that would actually help them improve.

“Fake it until you make it” works for building confidence or learning new skills, but it fails catastrophically with organizational practices. You can’t fake your way into genuine strategic thinking or meaningful retrospectives. The form without the underlying process is just elaborate procrastination.

From Performance to Purpose

Moving from dyspraxis to eupraxis requires intentional effort. Stop and ask yourself these reflective questions:

Does this practice influence our decisions? This is the most important question you can ask yourself about any team ritual or document. Genuine practices shape behavior and constrain choices. If you’re retrofitting practices to justify predetermined plans, you’ve just play acting.

What problem was this practice designed to solve? Reconnect every practice to its original purpose. If that problem no longer exists or this isn’t the best solution, stop doing it.

Who benefits from this practice, and how do we know? Identify real stakeholders with measurable outcomes. If you can’t name them or they report no benefit, you’re performing theater.

When did we last change this practice? Living practices evolve based on feedback. If yours looks identical to six months ago, you may be worshipping form over function.

Once you’ve reflected, its time to act.

Cultivating Phronesis

Dyspraxis is not a failure of best practices themselves, but a failure to embody their spirit. It emerges from the natural organizational tendency to optimize for the measurable and visible rather than the meaningful and valuable. The antidote is not to abandon structured practices but to approach them with the practical wisdom Aristotle called phronesis.

Leaders must cultivate eupraxis: intentional, reflective action that makes practices living tools rather than empty rituals. This means staying connected to purpose, building robust feedback loops, and being willing to adapt when context changes. The form matters only when animated by the wisdom behind it.

In a world of increasing complexity and rapid change, organizations cannot afford the luxury of hollow performance. The companies that thrive will be those that master the art of genuine praxis—where every practice serves a purpose, every ritual enables reflection, and every process drives toward meaningful outcomes. The alternative is an elaborate performance that convinces no one, least of all the people performing it.

A special thanks to Glenn over at https://substack.com/@statetransition for some early feedback on this article!

"A ritual without reflection is not praxis but pretense." - great point. I suspect some people never graduated from the schooling mindset. where you fill out the assignments and get a grade from the teacher. They go through these exercises because that's what they were assigned to do, they don't need a why beyond that.

Depending on your role combating organizational dyspraxia can be tricky. Some people like their theatre and won't appreciate you challenging it and trying to take it away from them. If you did that they might have to face uncertainty and (gasp) think.